Episode

Episode

· 07:11

This is Illinois Extension’s Voice of the Wild. In today’s episode we won’t be hearing an animal’s song and learning its voice. Instead, we’ll be giving voice to a tree. We’ll be hearing about Platanus occidentalis, the American Sycamore, and It starts with a walk through the woods.

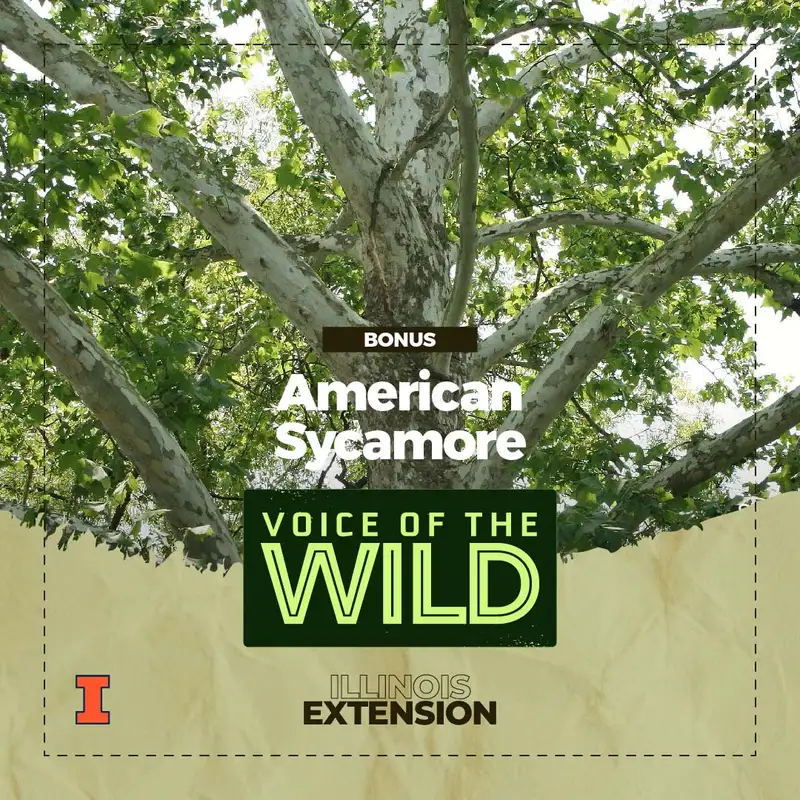

When sycamore trees are young their bark looks normal. Like every other kind of tree is brown and rough, though maybe a little thin. As the tree grows this bark flakes off and what’s left is the smooth and pale inner bark. On the sycamore this process of shedding to accommodate new growth can be strangely colorful; bark peeling away in progressive layers, first revealing tan, and then grey, and finally a creamy white. On an older tree your eyes can trace up the trunk and as you rise the mottled mix of brown gives way to a paleness….and by the time you reach the top the limbs appear as veins of white in a sea of green.

You may not notice at first but the Twigs of the American sycamore zig zag at their tips, and with a closer look you’ll see a strange umbrella of leaf tissue on the petiole of the leaves. A botanist might call that a perfoliate stipule, we’ll call it interesting.

A botanist would call the sycamore’s seeds (which come in spherical seedheads) “achenes” because of how the fruiting body shrivels up around the true seed and doesn’t break open as it dries. We could call the whole thing a buttonball. That’s what they used to be called: “button balls.” And folks called the whole tree a button wood. But whatever you call them; those spheres of achenes, the ones that don’t drop down in the fall anyway, are a favorite food for goldfinches and Pine siskins trying to stick it out through the winter.

Sycamores tend to drop a lot more than just their buttonballs. It’s a messy tree and it sheds like a dog. Like it’s got more wood and vegetation than it really knows what to do with: big leaves that must be raked, handfuls of sticks and zig-zagging twigs littering the yard, and occasionally a big, inconvenient limb.

And those big leathery leaves? They stick around. They can go a full year and half without breaking down too much. I usually say It’s good to leave the leaves….to not rake them all up and put them in bags at the curb…and I stand by that; leave the leaves to the spring at least. But if you live in a city where the leaves haven’t got much of a place to go and you’ve got an American Sycamore right above you? Well, you might have much of a choice come springtime. Those thick leaves will form a thatch that’s hard for anything this side of a shrub to get through – so you might a have to do a little raking to clear a path to the light.

This can all be a little rough for a city trying to keep the drains or even just the streets clear, especially after a windstorm. Some municipalities have banned both sycamores and their lookalike the London plane tree (itself is a hybrid of the American sycamore with the old world sycamore of Europe) but while some have turned away from these trees, most cities plant them in abundance. Especially the hybrid. It’s disease resistant and it's said that it tolerates pollution well. And both trees grow so fast you can plop them in a new neighborhood and have some good-sized trees in just a few years. They can be a pain but they bring such beauty and abundance they’re just too good to resist.

If you’re wondering if you’ve got a hybrid tree, well, it can be a little hard to tell but the hybrid trees tend have some more green on their inner bark, more deeply lobed leaves, and two buttonballs to a stalk instead of one.

But both drop big leaves.

No wonder the sycamore grows so tall and so fast; one of the tallest tree species in Eastern North America and certainly the widest. It's those great leaves eating up the sun.

In the wind those big leaves don’t tremble like an aspen or flutter like a maple; they’re just too big for that. They move like a thousand flags and the sound of the wind buffeting them is deep and slow.

We can infer something from those big dinnerplate leaves; this tree must use a lot of water. Each square inch of leaf transpiring away: pulling water up from ground, up the trunk, and right through pores in those big leaves. Yes, the sycamore tree must drink very deeply. And it’ll grow in lots of places but the place it really loves to be is right at the water’s edge. In bottomlands, next to creeks and streams. Anywhere its roots can drink all their fill from a water table that’s not far beneath. That’s where the sycamore is at its best.

Someplace where the leaves come down and instead of clogging up drains they blanket the ground with a fine insulation that protects the countless little lives making their way in the duff.

Someplace a heron might build a rookery. Or where the cavity left by last year’s fallen limb makes a good spot for a family of possums.

Someplace a tree might grow old and topple into the river.

Someplace a cluster of achenes might float away and take root in the mud.

This is the American sycamore

Voice of the Wild is a service of Illinois Extension’s Natural Resources, Environment, and Energy program. Thank you to our Marketing Team for equipping me with the tools of our trade. Emily Steele, Erin Knowles, and Matt Wiley; thank you.

An additional thank you to Dr. Brenda Molono-Flores for answering a tree anatomy question and to Dr. Joy O’Keefe for giving me some great suggestions. And shoutout to my coworkers Peggy Dotty, Ryan Pankau, and Layne Knoche for the conversations we had that got me thinking about the American sycamore. Many of the bird sounds I used today came from the Macaulay Library at the Cornell lab of ornithology.

This episode was written and narrated by myself, Brodie Dunn. Thank you for listening and if you really liked this presentation style, please let me know.

Listen to Voice of the Wild using one of many popular podcasting apps or directories.